The rivalry between master inventor Thomas Edison and visionary conceptual scientist Nikola Tesla runs through the Animal Engine Theater Company’s Age of the Android, and the mystery of what gears mesh or lock up in the clockwork of our lives, and what sparks of imagination leap free and which aspirations just fall into the void, are questions central to the play’s human drama.

The show (a rewarding experiment that ran for just three nights at first, Dec. 13-15, at The Secret Theater in Queens, NY), is composed of three overlapping narratives that the audience is divided up and walked through by actor-tour guides like a time travel theme park.

At Edison’s New Jersey complex in 1919, the next leap in human understanding—and, he hopes, the next act in his publicity saga—is at hand as he prepares to present his new invention, a sentient mechanical woman, to the public.

The three “tours” are each keyed to a character—Edison, “Ann” the droid, and Edwin Fox, a reporter invited to break the story. Cutting across these lifelines are Edison’s engineer Amelia Bachelor, newspaper magnate Moira Gish (both of them apparently sly composites of historical figures with similar names and ties to Edison’s interlocking enterprises), and Tesla.

Edison cares more about the industrial applications of Ann than the human potential, Bachelor has divided loyalties to Edison as a love interest and Ann as a sympathetic spirit, and Gish, called in to supply Edison with ink and funding, is a jaded elite who craves novelty and might surprise herself by trying once to do the right thing. Tesla recurs as a wrench-ex-machina at the moments of his rival’s next potential triumph.

The triple storyline at first seems like a stunt but soon sparks great intrigue in what machinations we might be missing, and reveals rich shades of motivation when you stay for more than one, as we all were invited to the night I attended. What you learn about what each character plans and why they do what they do tells much about the layers we build around all our personalities, and the levels that open up around past events when returned to with fresh eyes.

The triple storyline at first seems like a stunt but soon sparks great intrigue in what machinations we might be missing, and reveals rich shades of motivation when you stay for more than one, as we all were invited to the night I attended. What you learn about what each character plans and why they do what they do tells much about the layers we build around all our personalities, and the levels that open up around past events when returned to with fresh eyes.

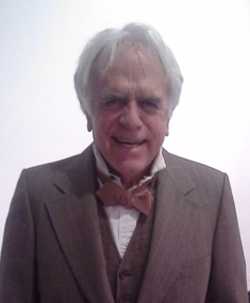

In a performance of flammable emotion and furtive intellectual poise, Bill Weeden plays Edison as a dotty Rotwang capable of titanic, desperate cruelty; he may be a master of making his rivals underestimate him as a professional, but he has no control of the profound disappointment he can foster as a man.

As Tesla, Timothy McCown Reynolds is the scary clown of the piece, in an astonishing turn of continental vaudeville that lets us at once see the petty buffoon his indignation presents him as and the wronged cosmic genius we know him to be.

As Tesla, Timothy McCown Reynolds is the scary clown of the piece, in an astonishing turn of continental vaudeville that lets us at once see the petty buffoon his indignation presents him as and the wronged cosmic genius we know him to be.

Tesla and Edison represent an Old World/New World wizard/mad-scientist dynamic that signals a transition in how we view technology, but neither is very smart at seeing the telling details in the big picture.

Carrie Brown gives a wise and moving performance as Ann, carrying herself like a music-box doll gaining its footing and learning humanity by asking everyone around her the questions we don’t ask ourselves. Bachelor—brought to life with remarkable focus in an emotionally precarious role by Nora Jane Williams—is a formidable female intellect nurtured by a new century whom Edison could relate to, while Ann is a feminine ideal created from antique notions whom he thinks he can control.

In a commanding projection of outsize pretense and shrewd humanity from Jennifer Harder, Gish is in her way as created as Ann, but with a bold persona she has assumed rather than the set of values Ann has had imposed upon her (a sisterly coincidence with interesting outcomes in one of the arcs).

Fox, in a magnetically contained portrayal of submerged trauma and restless dignity by Aram Aghazarian, is a WWI vet missing out on human comforts behind his emotional armor, while Ann is jeopardizing her security and maybe her existence as she seeks to lower the walls between herself and a possible human nature.

These couplets of personality counterpoint throughout the play and meaning proliferates, the dramatic mechanism precise and the possibilities of insight unlimited. I was sorry I didn’t get to see the third side of the triangle (the Edison and Ann-droid tracks being all there was time for on my night), but this theatrical concept has been designed to guide you to many dimensions you didn’t sense before. Staged for only the three nights, a revival is envisioned and an expansion, to even more character threads and thoughtfully imagined histories, is called for.

Writer Nick Ryan’s text shows an inspired grasp of what we know happened and instinct for what we believe could have; the cast co-creates their roles and reactions with 100 percent sincerity and spark; and Karim Muasher’s direction orchestrates the orbits of incident and interplay of identities and contrasts of perspective masterfully—the perky snark of the tour guides being his one tonal misstep; as with Reynolds’ Tesla, the strongest punchlines don’t know they’re being made. Still, trial and error is the essence of progress and bravery, and this play is far on the path to perfection.

In Animal Engine’s rational parable, the shortcomings of Edison as an old presumption are set against the horizons for Ann as a new idea. Our best qualities can’t just be built in nor our flaws engineered away. But Age of the Android casts an understanding and instructive eye on what it is we’re made of.

Adam McGovern’s dad taught comics to college classes and served as a project manager in the U.S. government’s UFO-investigating operation in the 1950s; the rest is made up. There is material proof, however, that Adam has written comicbooks for Image (The Next issue Project), Trip City.com, the acclaimed indie broadsheet POOD, and GG Studios, blogs regularly for HiLoBrow.com and ComicCritique and posts at his own risk on the newly launched Fanchild. He lectures on pop culture in forums like The NY Comics & Picture-story Symposium and interviewed time-traveling author Glen Gold at the back of his novel Sunnyside (and at this link). Adam proofreads graphic novels for First Second, has official dabblings in produced plays, recorded songs and published poetry, and is available for commitment ceremonies and intergalactic resistance movements. His future self will be back to correct egregious typos and word substitutions in this bio any minute now. And then he’ll kill Hitler, he promises.

The same way Justdial has introduced the Android application. Now get everything and anything at your fingertips

Except the elusive human heart, @marlonmark… :-)